Beyond Sugar and Spice - Preface & Chapter One: What Are We Made Of?

A lyrical beginning to a journey through the stories that taught us who to be - and how we might rewrite them.

This is the opening of my new book, Beyond Sugar and Spice: Rewriting the Scripts of Gender.

It begins, as so many of our stories do, with a playground rhyme - a small song that divided sweetness from strength and told us who we were meant to be before we could answer for ourselves.

Over the coming months, I’ll be sharing each chapter and interlude here - part essay, part meditation - tracing how gender was written into culture, and how we can begin to write it anew.

It starts here, with memory, and with the question that follows through every page:

Who decides what we are made of?

Preface

I remember the gloating sound before the words.

A circle of girls in the playground, skipping in rhythm, their voices rising in a chant older than any of us.

“Sugar and spice and all things nice…”

I laughed along, pretending not to hear the rest. “Snips and snails and puppy-dogs’ tails.”

It was meant as play, but it didn’t feel like it. I felt taunted - not by them, but by something invisible speaking through them. The rhyme told me what I was made of before I had any chance to decide. It told me I was rough matter, the unclean half of creation. I was told that boys and girls are very different and that I was the inferior one.

The girls sparkled, sugar-sweet and celebrated; I was the grit that made their brightness shine. I remember the jealousy most of all - and the anger that followed, the sense of being written wrong. I wanted to be seen as good, as gentle, as nice. But the rhyme had already chosen who could be those things.

That was my first lesson in gender. Not from a textbook, nor from parents or religion - but in play. From the way a game could carry an entire worldview. We were children learning lines that had been rehearsed for centuries, reciting the same spell that divided softness from strength, sweetness from strength, love from authority. It was a game - and an initiation. I didn’t know it then, but that playground song was history singing through us.

This book began there - with that small sting of shame and envy, with the question that followed me into adulthood:

Who decides what we are made of?

Every chapter that follows is an attempt to answer it. This book grew from that moment - a child’s confusion turned into a lifelong question. At first it was curiosity: why did such small words carry so much weight? But as I followed those echoes through history, religion, and politics, curiosity became a pilgrimage. Each chapter is a path back through the stories that taught us who to be - the rhymes, scriptures, and institutions that have written themselves into our bodies.

I do not write as a scholar looking down from a safe distance. I write as someone who has been shaped and sometimes broken by those stories. As a parent, I have watched new scripts form around my daughter and felt the old ones tighten around me.

These pages are not only about culture; they are about survival. They are about the imagination it takes to live between definitions, and the courage to keep rewriting what they mean.

The book is for my daughter, whose laughter reminds me what freedom sounds like, and whose presence has taught me that care is a form of resistance. Through her, I have learned to write not out of certainty, but out of hope - to imagine a world where children inherit not cages but possibilities.

And to you, whoever you are, who has picked up these pages: read them not only for what they explain, but for what they might awaken.

Gender is not destiny. It is story.

And every story can be told again.

- Mystes Arcana

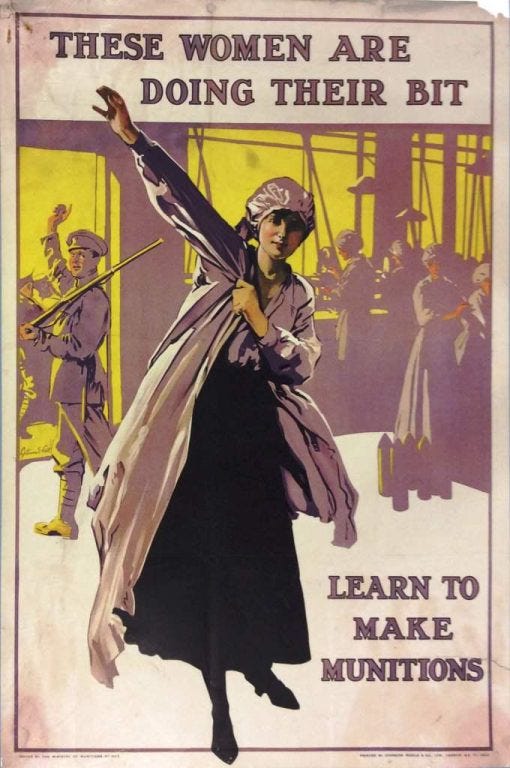

‘Sugar and spice had turned to steel and grit.’ Wartime poster, Ministry of Munitions, c.1916–1918. Public domain.

Part I - Origins: The First Scripts

Chapter One - Sugar and Spice, Snips and Snails

What are little boys made of?

Snips and snails, and puppy-dogs’ tails;

That’s what little boys are made of.

What are little girls made of?

Sugar and spice, and all things nice;

That’s what little girls are made of.

On the surface, this nursery rhyme is playful and innocent and presents itself as universal, asking, “what are little boys and girls made of?”. As I reflect on it’s meaning, I would like to take you with me, as I explore what lies beneath it. Let the discovery begin.

In it’s time, it reflected an upper and middle-class imagination of childhood. Families with the means to buy printed nursery books were the ones most likely to pass these verses down, and for them, childhood was sentimentalised as a time of innocence and moral training. Working-class children, by contrast, were rarely sheltered. They entered mills, mines, laundries, and workshops at the very age when rhymes suggested mischief and sweetness. The verse was less a description of children’s lives than a projection of adult ideals. It was a story written from above, exporting a classed vision of childhood that bore little resemblance to the daily realities of most working-class Victorian boys and girls.

But hidden within its sing-song verses was an entire worldview. Boys are messy, unruly, physical, destined for strength. Girls are sweet, docile, pleasing, and destined for patience and care. It was never “just a rhyme.” It was a cultural script - a story Victorian society told its children, shaping them for the roles that awaited them.

Children of the Factory Age

The earliest known version of the rhyme is often attributed to Robert Southey and first appeared in print in the early 19th century, though its exact origin remains uncertain. Like many nursery rhymes, it circulated in both oral and printed forms, blurring the line between folk tradition and literary invention. This was the dawn of industrial Britain, where children were not sheltered innocents but essential labourers. The rhyme’s imagery mapped neatly onto the workforce. Boys were sent into coal mines, chimneys, factories, and apprenticeships in heavy trades. Their jobs developed muscle, endurance, and toughness - the “snips and snails” of rough life. Girls were absorbed into textile mills, lace-making, domestic service, and sewing. Their jobs demanded dexterity, patience, and quiet obedience - the “sugar and spice” of docility.

Here lies a paradox. The rhyme painted children as sweet innocents of play, yet millions of working-class boys and girls lived another reality. They were not skipping through fields but bent over washboards, hauling coal, or stitching lace by candlelight. Childhood, romanticised in rhyme, was in practice an apprenticeship into hardship. The middle classes sentimentalised children in poems, paintings, and moral tales, while working-class families relied on their children’s wages for survival. The rhyme was not a mirror of reality but a mask - softening the brutality of child labour with the illusion of sweetness and mischief.

Training for Destiny

By embedding stereotypes into rhyme, society naturalised them. Child labour was not just exploitation; it was “training” for what boys and girls were supposedly made of. But twice in the 20th century, global conflict shattered this arrangement. When millions of men went to war, factories, farms, and transport systems had to keep running. Governments turned to women - and the rhyme was rewritten almost overnight.

During World War I, women were producing roughly 80% of the Army’s weapons and shells by 1917. Patience and care were reframed as industrial precision and patriotic duty. During World War II, women ran farms, drove buses, built ships, and assembled aircraft. In the U.S., the wartime figure of Rosie the Riveter rolled up her sleeves and declared, “We Can Do It! In Britain, women in overalls appeared on posters wielding tools with pride. In the Soviet Union, women went further by entering combat. The 588th Night Bomber Regiment, the “Night Witches,” flew more than 23,000 missions, terrifying German troops. Femininity was reframed not as fragility but as ferocity.

The rhyme’s sweetness turned into patriotism, patience became precision, its nurturing became national defence. Sugar and spice had turned to steel and grit.

Sugar to Steel

When peace returned, so did men. And with them, a new propaganda campaign. Women were thanked for their service, then urged to return to the home. The posters of women in overalls were replaced by smiling housewives in kitchens, new appliances gleaming around them. The nursery rhyme was quietly reasserted.

But something had shifted. Women had proven not just capable, but independent. They had tasted wages, skills, and new identities. The genie could not be put back in the bottle. The postwar backlash planted the seeds of mid-20th century feminism, which pointed to wartime labour as proof that gender roles were never natural, only imposed.

The Rewriting of Roles

The same dynamic of necessity reshaping gender roles has repeated across the globe. In Rwanda after the 1994 genocide, with so many men killed or imprisoned, women became heads of households, farmers, business owners, and politicians. Today, women hold over 60% of Rwanda’s parliamentary seats — the highest proportion in the world. Femininity was redefined as authority and responsibility. In Saudi Arabia during the 21st century, women went from being barred from driving to piloting aircraft. Hanadi Zakaria Al-Hindi - licensed in the 2000s and certified to fly in Saudi Arabia by 2013–14 - was the Kingdom’s pioneering woman pilot. In 2019, Yasmeen Al-Maimani became the first Saudi woman to fly a commercial airline service inside the Kingdom. Aviation, once the epitome of masculine daring, became a stage for women to symbolise modernisation itself.

In the 1940s–50s, women made up much of the ‘human computer’ workforce; the first ENIAC programmers were six women. Later, tech became male-dominated. Today, movements for diversity are reclaiming women’s place in a profession that was never inherently male.

Not only war and crisis, but culture too, has rewritten the rhyme. When the Spice Girls burst onto the scene in 1996, they dropped the “sugar” and kept only the “spice.” Sporty, Scary, Baby, Ginger, Posh - each embodied a different version of femininity, from athletic to glamorous to bold. Their rallying cry, Girl Power, was a deliberate rejection of docility. Girls could be cheeky, ambitious, powerful, and loud. Where Victorian society had used “sugar and spice” to confine, the Spice Girls turned it into a slogan of freedom. Pop culture had joined the long historical arc: the rhyme itself had been reclaimed, reborn as an anthem rather than a rule.

The Story Beneath the Story

The rhyme asked: What are little boys and girls made of? History has given many answers. When labour was cheap, children were shaped into workers. When war came, women became warriors and engineers. When peace returned, the rhyme was dusted off to restore order. And when new crises arose, it was overturned again.

From a nursery rhyme to global transformations, the arc is clear: during Victorian England, boys = strength and girls = sweetness. During the Industrial Age, the stereotypes justified child labour and divided work. During the World Wars, necessity flipped the script and women proved industrial and military equals.

Gender roles, then, are not biological destinies. They are stories societies tell themselves through rhymes, posters, propaganda, and pop songs. They have been used to divide, to mobilise, to justify - but also, in their flipping, to liberate. In truth, boys and girls, men and women, have always been made of the same raw materials: resilience, creativity, endurance, courage. What changes is not the substance, but the story.

Rebuilding the Rhyme

The image of men and women in the 1950s and 60s was not simply a return to “tradition.” It was a deliberate reconstruction of gender roles to serve society’s needs after the devastation of war. Nations sought to rebuild not only economies but also populations. The baby boom, with it’s surge of births from the late 1940s into the mid-1960s, became both symbol and engine of postwar recovery. Governments, advertisers, and media idealised the nuclear family as the cornerstone of stability.

Women were then celebrated as homemakers and mothers. Advertisements and magazines portrayed smiling housewives in gleaming kitchens, motherhood framed as personal fulfilment and patriotic duty. Domesticity was recast as essential to national survival. Men, on the other hand, were redefined as providers and protectors. Having a steady job, a wage to support a wife and children, a mortgage and car, became the markers of respectable masculinity. The breadwinner role anchored men to economic productivity and family responsibility.

This gendered division had clear uses for society. It encouraged higher birth rates to replace wartime losses. It fuelled consumer economies, driving demand for housing, appliances, cars, and schools. It provided social reassurance in the anxious Cold War era, where strong family units were seen as bulwarks against communism and instability.

But the rigidity of these roles planted seeds of discontent. Many women who had gained skills or independence during wartime now found themselves confined to kitchens and nurseries. Betty Friedan famously described this as “the problem that has no name” - the quiet dissatisfaction of women told that reproduction and domesticity were their destiny.

When the Children Rebelled

The very generation that the baby boom was meant to stabilise became the one to destabilise it. By the late 1960s, millions of baby boomers were coming of age, and they began to question the strict gender script their parents had embraced. The Youth Culture of music, fashion, and protest became tools of rebellion. Rock ’n’ roll, the counterculture, and mass university education gave young people a collective voice. The suburban ideal of the breadwinner father and housewife mother was rejected as outdated and oppressive.

The 1960s saw movements for racial justice, sexual freedom, and gender equality. Second-wave feminism, building on the frustrations of postwar women, challenged the structures of domesticity. Women demanded access to work, education, contraception, and political power. Men, too, felt the strain of changing expectations. In the U.S., the Vietnam War draft forced young men into military service, raising questions about duty and identity. More broadly, the breadwinner ideal no longer matched the growing desire for personal freedom and self-expression.

Divorce rates rose, women entered the workforce in greater numbers, and the nuclear family lost its aura of inevitability. The baby boom generation, raised on “sugar and spice” and “snips and snails,” had grown into adulthood with the confidence to overturn those childhood scripts.

The irony is striking: the demographic success of the baby boom created the mass of young people whose rebellion would crack the very social order it was designed to protect. What had once been presented as natural destiny - boys as providers, girls as homemakers - was revealed to be a fragile story, vulnerable to the power of numbers, voices, and collective imagination.

Rebellion into Reclamation

The upheavals of the 1960s and 70s cracked the gender order of the baby boom years, but the struggle over identity did not end there. The second-wave feminist movement had shown that the “sugar and spice” ideal was a social script, not a natural truth. By the late 20th century, a new generation would take that insight further, turning rebellion into reclamation. The Spice Girls made this shift explicit: Girl Power.

The Question Beneath the Rhyme

Every age rewrites the rhyme in its own language.

The words change - from nursery songs to slogans, from hymns to hashtags - but the question beneath them never fades: What are we made of?

For centuries, the answer was given to us. Now we begin to give it back.

The rhyme that once divided sweetness from strength has revealed itself as something else entirely - a mirror, not a rulebook. And when we look into it honestly, we find that what we are made of was never sugar or snails at all, but the same raw elements of being: tenderness, courage, imagination, and change.

Next, we turn to the other half of that reflection - the making of men, and the quiet cost of becoming what the world calls strong.

From rhyme to reflection, this journey continues

Next: The Making of Men — how strength became silence, and how it might yet become care. Subscribe to receive each new chapter as it’s written.

looks like a really deep and entertaining exploration… saw you on bluesky.. actually this article:).. followed the link. i began questioning beliefs (what we are told) and how it shapes us very young. now much older i write a lot to it. the undoing of conditioning.. gypsy-sprit. tethered-world. part of my life or memoir tag line. the other rise fall rise-my intuitive life. look forward to seeing where this goes… cheers:)!